Smarter emergency measures against COVID-19 needed to ensure lasting solutions in service provision.

Published on: 23/04/2020

The COVID-19 pandemic has meant that handwashing has made it to the front page of many newspapers. It’s the second time since the 1900s that there is a worldwide campaign on handwashing, for killing the virus and as a preventive measure to avoid spreading it further.

For a sector that has always struggled with getting attention for handwashing as an essential strategy to achieve better health in low- and middle-income countries, this is great news in sad times. However, there are other measures that governments are taking that run the risk of reversing the positive progress in the water and sanitation sector and setting it back 20 years.

To fight the pandemic, it is critical that water and sanitation services continue uninterrupted and that efforts are made to increase coverage. In a recent webinar hosted by the Sanitation and Water for All (SWA) partnership, several Ministers stated that among other measures they would be providing water for free for the next three months (i.e. Burkina Faso, Ghana, DR Congo).

The governments of many countries are also ensuring that there are no disconnections from services caused by non-payment, that there are tankers distributing water, that there are hand sanitisers available in public institutions, etc. (i.e. Bangladesh, Burkina Faso, Ghana, Uganda, Colombia). One of the most asked question on the webinar was ‘how will this be paid for without bankrupting the utilities?'. A crucial question!

Colombia was a country with an answer, the government has directly supported utilities so that more than one million people that had been disconnected from the services were reconnected.

Many countries are also working with utilities and the private sector to deploy mobile handwashing facilities as seen in Kenya, Rwanda (and mentioned at the SWA webinar by the governments of Nigeria, Bangladesh, Malawi, Ghana).

Critically, those without access to water and sanitation are not benefiting from most measures and are once again being left behind.

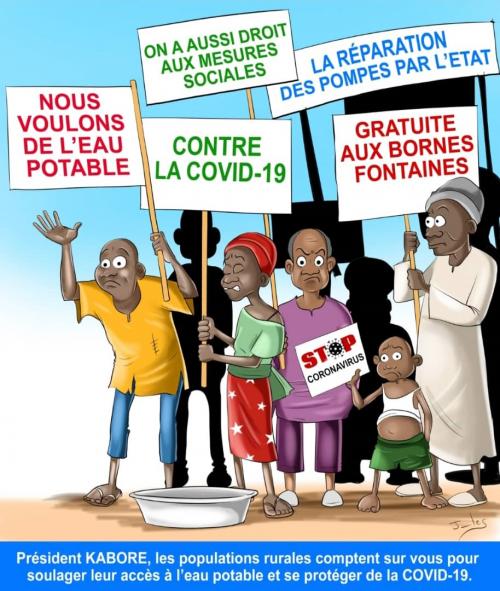

In Burkina Faso, all the measures around free water concern the main national utility’s (ONEA) network, but ONEA operates mainly in urban areas and in most urban centres where the population can pay for services. Yet, in rural areas the curfew stopped those in poor areas from accessing communal fountains that only flow at night during the dry season.

Cartoon by André Jules Nikiema

In South Africa, in the Madibeng municipality, taps have run dry for years, making it difficult for the population to stay at home and remain at safe distance while accessing the available boreholes.

In Kibera, the largest slum of Kenya, hundreds of thousands live in close proximity, they share water taps and toilets, these are managed by private operators and the population in this area pays more for water and sanitation than those that have water and toilets in their houses.

In Ghana, the Ghana Coalition of NGOs in Water and Sanitation (CONIWAS) has called on the government to ensure prompt payment to service providers to ensure they do not suffer financial stress, which could affect the systems in the future and threaten sustainability of water supply

First, the emergency response teams need to identify the most vulnerable populations that do not have access to water and sanitation services and are at risk: those living in densely populated informal settlements, street dwellers, those who rely on daily wages, highly populated rural areas, migrant workers, internally displaced persons, citizens with disabilities, etc. Support can be targeted to hotspots and institutions working in these areas. This article from the World Bank provides a good overview of measures being taken in Latin America and the Caribbean.

Source: Mdogo

Second, governments need to ensure that water keeps running, that there is continuity of water and sanitation services and provision of handwashing facilities and safe disposal of waste. When budgets are tight, this can be done if those that can pay for water and sanitation services continue to pay to ensure that utilities have the required funds available to protect their staff and maintain the existing facilities. When providing water for free, ensure that there are ring-fenced funds available and transferred to the water utilities, to ensure their operations are not compromised. In most countries, key staff in the drinking water production and wastewater processes are also being exempted from travel restrictions, as they play a vital role.

Third, national governments should transfer the required financial means to the hotspot areas so that local governments can immediately provide the support required for health and hygiene responses, including setting up emergency clinics fitted with handwashing facilities.

Fourth, states need to provide CSOs with their legitimate space, so they are able to play their part. In some countries, the state of emergency has meant the suspension of civil liberties. In other countries, national coordination committees are being set up which do not include members of civil society organisations. Civil society can play a key role in preventing the spread of misinformation and create awareness using local radio stations. In times of conflict, when there is less water available, the higher the corruption risks that emerge from attempting to control the water supply. Civil society can bring forward sensitive issues impacting the most vulnerable. This is therefore a critical time to deepen the engagement between states and citizens.

And finally, water and sanitation experts can support public health experts to champion the urgent need to tackle social inequalities – both as a requirement for generalised public welfare and in the measures taken to tackle the pandemic.

“The best response is one that responds proportionately to immediate threats while protecting human rights and the rule of law.” António Guterres, Secretary-General of the United Nations

In order to prevent that the progress that has been achieved in the past 20 years - improved access to water and sanitation, more sustainable utilities, more marginalised areas with reliable basic services, better health, less burden for women and children – is lost, the emergency measures need to be anchored on building resilience and supporting governance systems and institutions to implement lasting solutions in service provision.

The sector will need lots of public and private finance to recover after COVID-19, so we need to make sure that during the emergency phase the money is spent wisely.

At IRC we have strong opinions and we value honest and frank discussion, so you won't be surprised to hear that not all the opinions on this site represent our official policy.