During the Thursday morning monitoring and learning session at IRC's All systems go! participants discussed factors than enable or hamper use of monitoring data in evidence-based decision making.

Published on: 03/04/2019

During this session, the two small Ethiopian towns Jinka and Wukro were used as examples where utility staff produce monitoring data on an ongoing basis. The data is compiled and shared with the utility management as well as with the Water Board and the Regional Water Bureau overseeing and supporting the utilities. On a periodic basis, utility data is collected and compiled at national level, e.g. as part of the National WASH Inventory (2011 and 2019) or IBNET data collection. The data can inform decisions taken by utility staff and management (service provider level), by Water Board members and Regional Water Bureau staff (service authority level) and by policy makers and development partners (national level). But, does that really happen? Is monitoring data actually used to inform decision-making processes at these different levels?

Monitoring data can in theory be used for “improvement”, informing operational, strategic, regulatory and policy decisions, as well as for “accountability”, both upwards (e.g. customers holding service providers and duty bearers accountable for their performance and/or provided services), as well as downwards (e.g. financiers holding governments or service providers accountable for the way in which money has been spent). However, exploring the actual use of utility monitoring data in informing decision-making processes at different levels inJinka and Wukro showed limited use of this data, especially at authority and national level.

LEVEL | USE FOR IMPROVEMENT | USE FOR ACCOUNTABILITY |

National level | No use | Limited use |

Service authority level | Limited use | Limited use |

Service provider level | Use | No use |

This begs the question: What are the factors than enable or hamper use of monitoring data in evidence-based decision making and how do they do this? This question is not only relevant for these two Ethiopian towns, but also for the wider water supply sector, where we have seen an increase in the availability of (monitoring) data over the last decade, but limited use of this data in informing decision-making processes. Having a deeper understanding of this may help us to improve the use of monitoring data.

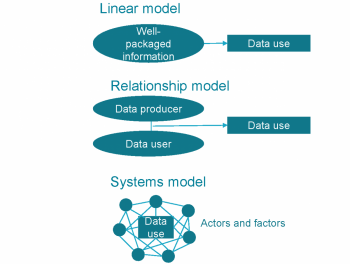

Three models for understanding the factors that contribute to whether or not monitoring data is used, were presented (based on Best et al (2009)’s overview of models for understanding knowledge in use in the health sector). The linear model assumes that data will be used as long as data is converted into well-packaged information. The relationship model assumes that linkages and relationships between data producers and data users will determine whether or not monitoring data is used. The systems model recognises the importance of well-packaged information, and of the relationships between data producers and data users, but it perceives these to be part of a wider system of actors and factors that influence whether or not monitoring data is used, set within a wider (political-economic) context. Naturally, at IRC’s Systems symposium, we focused on the systems model.

So first, let’s have a look at three clusters of factors that (I believe, based on literature and interviews) can enable or hamper the use of monitoring data: data characteristics, (individual, organisational and institutional) capacities, and motivations. The table below presents these factors and their definitions.

Back to Jinka and Wukro to see whether assessing the strengths of these factors can provide us with insights in why data is or isn’t being used. The table below gives an indicative overview of the strengths of the factors at different levels, which shows that overall the factors are assessed as weak / low. This could account for, or at least contribute to low use of monitoring data, especially at service authority and national level.

In addition to assessing the strengths of the factors, it is important to understand how the factors influence the use of monitoring data. A poll on the most influencing factor showed a more or less even distribution in people believing data characteristics and motivation to be the most influential factors. Within the data characteristics, the majority of voters believed data timeliness and accessibility to be key factors influencing use of monitoring data.

In addition to a direct influence, factors can have an indirect influence on the use of monitoring data, by influencing other factors. Understanding how factors influence each other can give us insight into the “leverage points”, which can be useful to target when attempting to improve the use of (monitoring) data in evidence-based decision making.

Inspired by the “factor mapping” methodology developed by the University of Colorado Boulder (which they presented at the Systems Symposium), I have started looking at influence and dependencies (MICMAC analysis) and level of centrality of the factors. Initial analysis seems to suggest that it is not all about the data. Of course, accessible, sufficient, relevant, timely, good quality data is important, if decisions are informed by this data, but incentives, culture, and individual, organisational and institutional capacity can serve as leverage points for strengthening the use of monitoring data.

The participants of the session confirmed this insight by ‘voting with their feet’: when asked to position themselves in a place which they perceived to represented the (combination of) most (directly and indirectly) influencing factors, the picture in the figure below emerged. It shows that data characteristics, although important, are not believed to be the most influential factors affecting whether monitoring data is used or not. The interface between data and capacity, and between data and motivation, the leveraging role of capacities, and especially the interface between capacity and motivation were indicated as highly influential by participants.

Focusing only on getting the data right will not lead to better evidence-based decision making. There is a need to also address incentive structures (including regulatory frameworks and staff performance mechanisms); institutional capacities; individual capacities; and organisational capacity, especially in contexts where these are not strong, like the Ethiopian towns Wukro and Jinka. These factors can present useful leverage points for improving data and use of data.

This blog is based on the presentation by Marieke Adank (IRC) and groupwork at the monitoring and learning session during IRC’s Systems Symposium on 14 March 2019. This session was organised by Heather Skilling (DAI), in collaboration with Brain Banks (GETF), Nick Dickinson (WAHSNote) and Marieke Adank (IRC). The presentation, including the result of the interactive exercises and group work can be found on SlideShare.

At IRC we have strong opinions and we value honest and frank discussion, so you won't be surprised to hear that not all the opinions on this site represent our official policy.