A new and bold way of thinking is needed to change the way in which water, sanitation and hygiene services are provided.

Published on: 24/02/2014

By Patrick Moriarty and Harold Lockwood

For the last six years or so, primarily through our WASHCost and Triple-S initiatives, IRC has engaged deeply with the challenges of what it takes to provide sustainable water, sanitation and hygiene services. We think that we've identified many parts of the puzzle (and so have many others working in the same direction – we're keenly aware that we're not the only show in town) and we've been sharing these regularly through our websites, papers and blogs. But, what does it take for these piecemeal findings to be taken up and to lead to wholesale change: ensuring that the post-MDG goals of universal access with sustainable WASH services can be achieved by 2030?

The evidence is mounting that despite decades of investment and the efforts of thousands of organisations, the rural WASH sector in particular is not delivering

Over the next few weeks, in a series of blog posts, we will be attempting to set out and explain our "big message" about enabling, supporting and driving change across the whole WASH sector: about how to tackle the entrenched – and deeply inter-related – problems that lead to failure of water, sanitation and hygiene systems to deliver to users over time.

In this first blog we set out our call to action and explain why we need to go for a new and bold way of thinking to make change happen. Subsequent blogs will introduce and articulate the approach to change, which is deeply rooted in an understanding of a WASH sector as a complex and adaptive system. We will share our experiences of how to achieve this change in practice – what are the steps and phases, what does it take to catalyse such change and how long does it take? For this we will draw on our deep experience in Ghana, Uganda and other countries over the last five to six years.

In the final blog instalment we will set out a challenge to other like-minded partners: what it will take to make this change a reality, making explicit linkages with various on-going initiatives and national sector processes.

The last decades have seen more people lifted out of poverty than at any time in human history. Indeed, according to Hans Rosling, the end of absolute poverty is achievable within a couple of decades. Where China and the others countries of East Asia have led, others will follow: richer, more stable, better governed. And in the world of water – and to a lesser extent sanitation and hygiene – we have made amazing progress in the last decades as well, more than matching population growth with 2.1 billion people gaining access to an improved source of water since 1990.

Yet as access to mobile phones moves steadily towards global saturation, in much of water, sanitation and hygiene we remain stuck in decades-old paradigms of supposedly appropriate technology and community management that – when looked at in detail – is failing to provide services fit for a richer, better educated and more modern world with higher expectations.

The evidence is mounting that despite decades of investment and the efforts of thousands of organisations, the rural WASH sector in particular is not delivering. It is not delivering services to all; the services that are being delivered are not sustained over time; and, in too many cases, the services are not even meeting the most basic requirements. The graph below, taken from IRC research on rural water supply in Ghana, is indicative of the problem.

The top of the bar charts – in red – shows the figures for 'non-functionality' and are typical of those reported extensively elsewhere. But we would argue that just as important are the figures for service delivery (measured in terms of quantity, quality, reliability and accessibility) that lie below – and according to which as few as 2% of people actually access an acceptable level of service, according to the country's own standards (the gold blocks at the bottom of the columns).

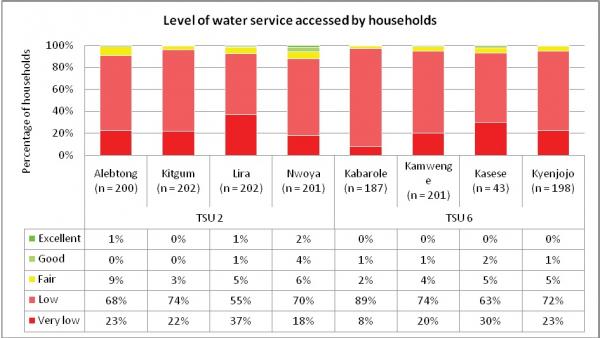

Another recent IRC study in Uganda tells a similar story: there, only between 3 and 12% of people in the districts studied are receiving a service that meets the country's basic norms. Below is a graph from that report. The portion of the column in red denotes very low service (users don't have an improved source within 1km) to low (users access a service that doesn't meet one or more of the standards for quality, quantity and reliability). Note that the majority of users are in the low category—they have service, but it's bad service.

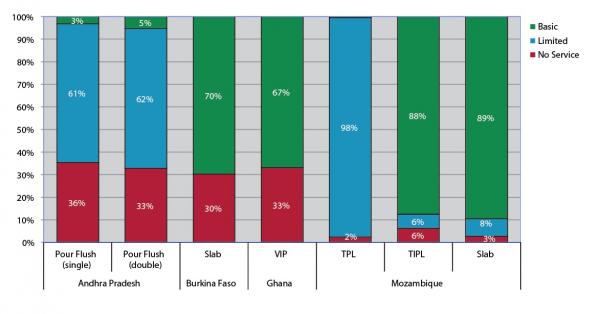

These figures are for rural water. But similar evidence exists for sanitation: latrines collapse or fill up. Sewage is not treated and is dumped into water courses, open-defecation free communities slip back into open defecation again. The next graph shows results of IRC research on rural sanitation service levels in India, Burkina Faso, Ghana and Mozambique. The highest level found was "basic" – meaning that the service met country standards for distance and environmental protection, but with unreliable O&M and irregular pit emptying.

These failures are driven by a number of factors, many (arguably all) of which can be linked to the broader political-economy of aid and to the low status that (rural) WASH – particularly sanitation and hygiene – have traditionally suffered. These factors include: weak government leadership; a high degree of fragmentation made worse by an over-reliance on one-off projects; divergence of priorities often driven by external aid agendas; a focus on delivering new hardware rather than on operating and maintaining what is already there; lack of political commitment and related chronic under-funding by government, particularly of management related aspects of service delivery where the focus remains on construction.

Our approach to change is premised on an optimistic and forward looking perspective, one in which government is the legitimate overseer of service delivery – not an inconvenient or obstructive force to be ignored or worked around.

The result is that in many developing countries, national WASH sectors are dysfunctional, lack a coherent vision and the right policies, capacities and investment plans to deliver true services. If we are to meet the post-MDG goal of universal access by 2030-40, we need to change how we do business: from only delivering water and sanitation hardware to delivering hardware and the management and governance systems that provide great services that last. The question is how to do this: how to deliver change across the whole complex and interlinked system of actors, institutions, resources and relationships that makes up what we all know as "the WASH sector"? And how to make that change irreversible and scalable.

Over the last decade IRC and our partners have developed a wealth of experience (backed by a suite of tried and tested tools and approaches) on how to drive and support change across the whole system that is the WASH sector: change that leads to better services for the poor.

Our approach to change is premised on an optimistic and forward looking perspective, one in which government is the legitimate overseer of service delivery – not an inconvenient or obstructive force to be ignored or worked around. We are convinced that in a world of rapidly increasing prosperity and improving governance there is no reason that people who have mobile phones should not have access to good quality water, sanitation and hygiene services too. Achieving this vision is primarily about changing expectations and behaviours, and leveraging resources that already exist, as well as using them differently.

In our on-going dialogues and engagements with many individuals and institutions in the sector, there now seems to be a broad and wide acceptance of this end state and of the need to move from focussing on provision of hardware to providing hardware as the first step in delivering services that last. Indeed, for many it is a "no-brainer". So the real challenge is then to explain how we can get there in a complex world, where any one single organisation only sees one part of the puzzle.

At IRC we have strong opinions and we value honest and frank discussion, so you won't be surprised to hear that not all the opinions on this site represent our official policy.