In Asutifi North district in Ghana, the District Assembly is making a bold attempt to achieve district-wide full coverage by 2030.

Published on: 27/11/2019

IRC and a range of other partners are collaborating on a plan led by the District Assembly to transform a historically low level of service. Drilling is already taking place and communities are engaged in forging a new relationship for shared responsibilities. If the plan works, then by 2030 everyone will have at least a basic level of water and sanitation service and most will have a great deal more.

The future is bright, maybe. But if the future is going to be great, why was it not great before? We do not have to look behind us very far to see how awful things have been. Rewind to March 2018, just before the launch of the ANAM (Clean Asutifi North) initiative. More than half of families in the district lacked access to improved communal water services, with the greatest deprivation in poorer and rural areas. Fewer than one in six households could access an improved household latrine. When the District Chief Executive Anthony Mensah conducted a tour of communities to see for himself, almost every community complained to him about the quantity or quality of their water – often both. They were very pleased to see him - but they wanted action.

Vida Duti, IRC Ghana Country Director, speaking at the launch event of the Asutifi North Master Plan.

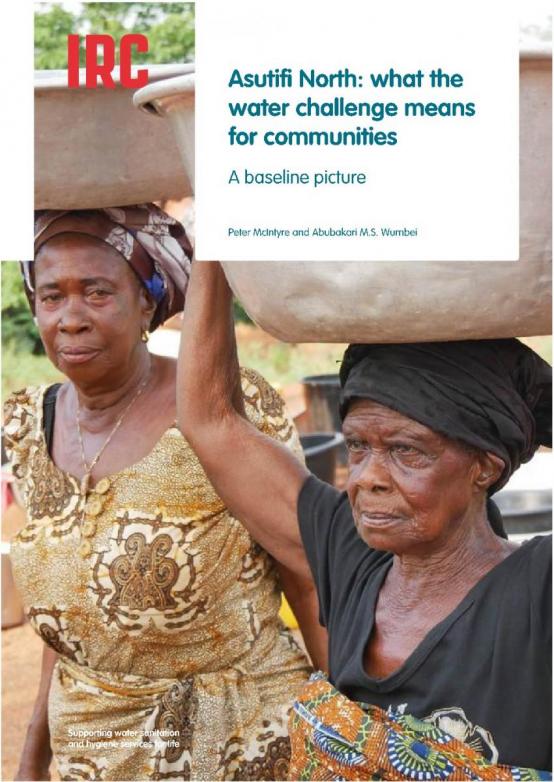

Facing up to the worst conditions is part preparing to turn things around. As Vida Duti country director for IRC Ghana puts it: “Having the baseline in place, will help everyone involved to understand the strengths and weaknesses of the current WASH systems and service levels, and what we need to do to improve them.” And there have been many weaknesses. They are shown by short videos and a booklet produced after district planning officers led a team to document conditions in some communities facing the most serious problems. The most striking feature is the extent to which low levels of WASH services devastate everyday lives, particularly for women and children. They do not experience water and sanitation as a ‘sector’ – but as part of the daily fabric of existence. When the water supply breaks down everything is put on hold. Failure disrupts every attempt to bring about improvements.

Asutifi North: what the water challenge means for communities

In Tawiahkrom, Lydia Adjei used to go to the well at midnight in the hope of finding water before morning. She recalls repeated failed attempts to improve the supplies. “You dig for water, it collapses, you dig and it collapses,” she said. Now she sees their one remaining successful well being put at risk as it has become a magnet for five communities in the area.

In Agravi, the supply is entirely powered by women standing on the lip of an open well and heaving up buckets with a rope. If they don’t arrive early, they don’t get water.

In Wamahinso, a fierce argument broke out after the pump stopped working during the documenting visit. Women had waited all morning without success. When they returned in the afternoon and the pump stopped working again the video below shows their reaction.

The small sums they collect for water in Goamu Asamang do not cover the costs of repairing frequent breakdowns. Sometimes women with babies on their backs walk three miles to fetch water from the next village. The sheer physical labour for women of carrying water home twice a day is – as in so many places – a striking feature of their existence.

Every community knows the history of its water supply and they are acutely aware of repeated failures. They can point to many wells and water points provided by the District Assembly or NGOs that are no longer in use. They know how their children often do not even get to school when there is no water in the morning.

The situation for sanitation is even worse. Crumbling toilet blocks, open defecation, social embarrassment and even snakes in the pit are all part of the picture.

Some community leaders recall the time when their parents and grandparents obtained water from traditional streams. Service levels in those days were extremely low but there was at least a degree of self-reliance. Communities welcomed past efforts by the District Assembly and NGOs to provide better wells and latrines, but they came to associate these services with outside intervention. There are today few signs of effective community management or regular payments for upkeep. Communities were never true partners in their development of these services, but they become the sole partner in suffering when they fail. The level of dependency was ingrained and almost every interview concluded with a plea for outside help. In one community people even said they lacked the skills to make a lid for their open well.

Ghanaians are famously optimistic and hardworking and these farming or mining communities are adaptable and resilient. Their commitment and determination are clearly visible in the short videos. Dependency is not natural but seems to have been learned from their experience of facilities as donor gifts. The challenge in Asutifi North is therefore not only a physical transformation but one of building capacities so that communities can share in solutions rather than only in problems. Many of the community leaders are ready for change. Chief Nana Amoah Baafi in Goamu Asamang says: “For all these villages what we see is that for schools, water and other things it is the District Assembly that helps us and NGOs also come to help. [But] if it falls on us to do something the entire community will deliberate, and we will also help.”

The booklet is a quick read – the videos are only 3-5 minutes long. It is worth watching and listening to what people in these communities have to say in these snapshots of everyday life.

Putting these experiences permanently into the past can be a true legacy of the Asutifi North initiative.

At IRC we have strong opinions and we value honest and frank discussion, so you won't be surprised to hear that not all the opinions on this site represent our official policy.