Sanitation workers deserve safe working conditions through legal protection and operational guidelines.

Published on: 12/12/2019

Sanitation workers in Siem Reap, Cambodia, do you think vac truck operators are following prescribed Operating Guidelines, and wearing the right personal protective equipment to sufficiently manage their exposure to untreated faecal waste? (Photo credit: IRC)

Sanitation workers are some of the most vulnerable workers, exposed to serious occupational environmental and health hazards. For World Toilet Day, the World Bank, ILO, WHO and WaterAid released this report on sanitation workers, with case studies of manual emptiers, septic truck operators and sewer cleaners, and pleading for better working conditions for these (public) service providers (whether formal or otherwise).

They are the women and men working to clean, maintain, operate and empty sanitation facilities, whether pit, sewer or treatment plant. This includes:

Deaths of sanitation workers are all too common, with headlines like these from India: “Swachh Bharat reality: A death every third day in gutter” and “In India, a sanitation worker dies every 5 days. Here’s how to change that.” Sanitation workers often work invisibly in the dead of night and their health issues, injuries and deaths go uncounted. Not just in India, also listen to stories from workers from Burkina Faso and Tanzania.

Sanitation workers are exposed to health risks associated with physical, chemical and biological hazards such as:

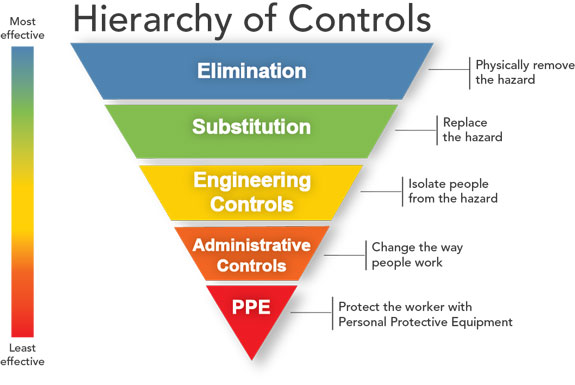

“Since micro-organisms are an inherent part of sewage, this hazard cannot be eliminated” and needs to be managed through engineering controls, administrative controls and/or personal protective equipment. (Health and Safety Executive, 1995)

Photo credit: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/hierarchy/default.html

Importantly, the legal protection offered to sanitation workers is generally weak, and there is minimal enforcement and oversight of laws, policies and standards protecting their rights and health. Operational controls, like Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs), are often missing and where present, may not be enforced. (World Bank, ILO, WaterAid, and WHO, 2019). Here are two example SOPs: Cleaning of Sewers and Septic Tanks from India and Municipal Faecal Sludge Management from Gujarat.

The Health, Safety and Dignity of Sanitation Workers report outlines four steps that could form the basis for how we can achieve better working conditions for our Sanitation Workers:

Sanitation workers deserve legal protection and safety and health standards to be able to work safely, and with dignity and have their health protected.

SDG target 6.2 for safely managed sanitation does not specifically define the conditions under which sanitation workers should perform their tasks, however, safely managed means that sanitation related facilities and services need to be safe for the users, the sanitation workers, and the environment.

Importantly, even when countries are not on-track towards 100% safely managed, steps can be taken to allow growth towards this target. For example, by-laws/building codes can set technology standards: e.g. off-set pit (instead of pit directly located below slab) with mandatory access point for vacuum trucks. Already thinking about how the facility can be best emptied safely will translate into less precarious conditions for workers later on. This is what we see as an important addition to the report’s recommendation.

In terms of sanitation systems strengthening, sanitation workers are an integral part of the overall sanitation system. Through regulation and health and safety standards the job of sanitation worker can be formalised, and the workers protected. Monitoring and enforcement can ensure that employers comply with health and safety standards and operational guidelines.

However, we should not be fooled to believe that a formalised workforce is the solution. Bezwada Wilson, advocate for the rights, protection and dignity of Sanitation Workers in India, said it right: “Whatever the wages, whatever the safety gear, human beings should not clean other people’s shit.”

At IRC we have strong opinions and we value honest and frank discussion, so you won't be surprised to hear that not all the opinions on this site represent our official policy.