The world will not reach the sanitation Millennium Development Goal. There are still 1 in 3 people worldwide without access to safe sanitation. Within 15 years we want universal sanitation coverage and we know that we need to do something drastically different to reach scale and to reach the poorest.

Published on: 30/04/2015

The BRAC Water, Sanitation and Hygiene programme and related BRAC programmes have substantially increased the number of people with access to water, sanitation and health. By increasing awareness at the household level and empowering people at community level, BRAC supported the sanitation movement in Bangladesh. Over the past 8 years, the BRAC WASH programme reached more than 66 million people, about half of the rural population of Bangladesh.

The approach is known to many: put a lot of emphasis on hygiene promotion to create demand for hygienic latrines, keep doing hygiene promotion year after year. Make sure to reach all: poor and non-poor; and not only women and children, but also men and adolescent boys. At the same time, build the capacity of local entrepreneurs to be able to deliver the latrines that everyone wants to buy and support finance options for families that want to take loans to build the latrines. Additionally, identify the poorest of the poor and provide them with a subsidy so they can build sturdy offset pit latrines. Then, do this all over Bangladesh year after year, building the capacity of staff to deliver better programmes over time, creating economies of scale and reducing costs. Simple, right?

To understand if the toilets provided were affordable to the poorest, the BRAC WASH team in Bangladesh, with the technical support of IRC, has analysed the spending of 1,000 households with latrines older than three years which were well-maintained and hygienic (with a pit, superstructure and water seal) in the Bagherpara district. For downloading the full report see links below.

Half of the latrines were self-financed by the households themselves, the remaining were covered all or in part by a subsidy to cover construction costs. The subsidies were only given to the ultra-poor, not to the poor - to whom micro loans were made available. By both international and Bangladesh standards both the poor and ultra-poor in the study area are below the lower regional poverty line.

The first relevant finding is that the BRAC WASH programme had a catalytic effect on the number of ultra-poor having access to a toilet. The ultra-poor have built mostly double pit toilets (which are covered by the grant agreement), while the poor build mostly single direct pits. The non-poor build mostly septic tanks and single off-set pit toilets. The poor spend about US$ 45 for latrine construction per household (5 people) while the non-poor spend US$ 375 per household.

The cost of regular, smaller maintenance is the responsibility of households. This includes mostly cleaning products. The typical annual operating expenditure is US$ 5 per year per household for the ultra-poor households and US$ 12 per year per household for non-poor households.

The cost of maintenance such as pit emptying and eventual renewal of latrines is also expected to be covered by households. Ongoing expenditure required to maintain a reasonable sanitation service can range from almost nothing to US$ 1.4 per year for single pit latrines in an area where pit emptying has to take place every 2-3 years. The ultra-poor and poor incur more costs with superstructure replacement, while the non-poor spend most on making their facilities stronger and prettier with tiles.

The costs incurred by households for building and maintaining latrines which remain hygienic and used years after construction in Bagherpara are therefore on the lower end of the WASHCost international benchmarks – but still within them.

Although the expenditure by the BRAC WASH programme was specifically allocated for the construction of toilets for those classified as ultra-poor, the entire communities were mobilised and encouraged to change behaviour. For each dollar spend by BRAC WASH targeting the poorest, in return, the poor spend US$ 18 per person in latrine construction and about US$ 2 per year per person for maintenance which is great value for money.

These support costs are substantial compared to other programmes assessed in WASHCost. The majority of these costs are the salaries of permanent staff in Bagherpara.

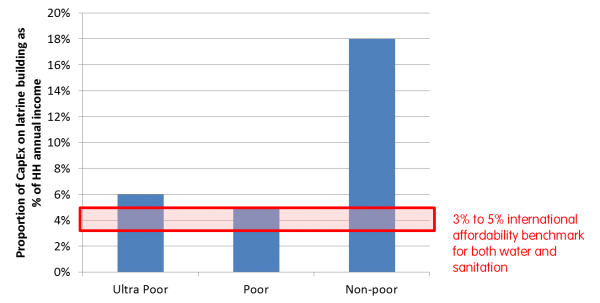

We have used the reported household income for an affordability analysis in the intervention area. In a previous blog I have explained the limitations of using reported income to analyse affordability and although the results are indicative only, they are useful to support programmatic improvements.

In the intervention area, we found that the costs for a double pit or double off-set pit latrine can be up to 6% of the reported household income of the ultra-poor. It is clear from the data that without the BRAC WASH subsidy for latrine construction, these are not affordable for the ultra-poor.

The amount being spent by the poor on latrine construction also clearly exceeds the international benchmarks, reaching 5% of household reported income which demonstrates a high willingness to pay for improved sanitation facilities but might keep many families away from buying a latrine - even if they have access to the micro loan scheme.

The good news is that the maintenance costs, including the regular emptying costs required to deliver a basic service are affordable even to the lower socio-economic groups.

The progress seen over the lifetime of the BRAC WASH programme clearly demonstrate that in the long term, continuous investment in behaviour change and demand creation leads to sustainable use of hygienic latrines. However, if service levels are to be maintained over time and to get the most out of the investments made, it is essential that households, donors and programme managers understand how much is required to meet the ongoing, recurrent costs of service delivery and who will fund them.

A reduction in the BRAC WASH grant will lead to less coverage for the most vulnerable groups of the population: the ultra-poor. In addition we also argue that a grant component or other financial mechanism needs to be extended to the poor beyond the micro loans. A small grant to the poor to support latrine construction could be catalytic and contribute to high coverage rates since the largest absolute number of the population in Bangladesh falls under this category (46 million people in 2010 with about 65% in rural areas).

Both the poor and the ultra-poor will soon be faced with the inevitable investments required to empty latrines and replacing some of the infrastructure. This means there will be demand for sanitary services, through the provision of pit emptying/disposal services, ongoing hygiene promotion, waste management etc. These services may form part of the support from institutional bodies or be incorporated into services already purchased by households.The process seems straightforward, however the service delivery options mentioned are not yet existing beyond programme implementation. The remaining challenge is to reach those that are not reached yet: the hard-to-reach and those living in areas which get flooded seasonally. This will be the next challenge for BRAC WASH.

At IRC we have strong opinions and we value honest and frank discussion, so you won't be surprised to hear that not all the opinions on this site represent our official policy.