To deliver water and sanitation services sustainably over time requires a structured process of change to align sector actors and help them work together effectively – in essence to change the whole system, rather than focusing on strengthening individual institutions, policies or practices.

Because of the number of activities and actors involved, water and sanitation service delivery is inherently complex. And as much as we may be drawn to the idea of straightforward technological or market-based solutions, this complexity means such solutions will never get us all the way to sustainable services for everyone – particularly for the poorest people in the hardest to reach and most remote areas.

It is not enough that one individual or organisation begins to perform better or that an improvement is made in some technical aspect of service delivery. The whole system of individuals, organisations, technologies and the institutions (political, financial, and regulatory) that link them needs to work more effectively. This is a messy reality with many incentives at play involving both national politics and the politics of aid.

Effectiveness in such systems starts with alignment, and alignment in turn comes through a shared vision or purpose – often requiring significant investment in understanding and 'accepting' the problem or challenge as a first key step.

But alignment of efforts also requires the alignment of incentives. Put simply, if the money in WASH is primarily focused on building hardware, then WASH actors will deliver hardware. If, instead, we want them to deliver good quality services, then we must pay them and assess them on their ability to deliver good quality services.

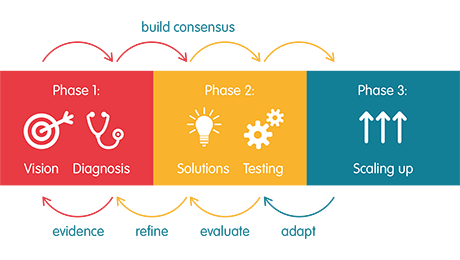

Over the past five years IRC has worked hard on driving and supporting change in rural water supply in Ghana, Uganda and other countries. From this experience we are starting to see the outlines of a replicable process for driving change emerge. It is important to stress that the precise details and, most importantly the pace of change, will vary across different country contexts, but our experience points to three broad phases, which are summarised in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1: The phases of change

Phase 1: is all about creating shared perception of the need for change: the vision. In practical terms this means carrying out (or collating existing) research into the current state of water (or sanitation) service provision and then bringing this evidence to the table to trigger interest in and demand for change: the diagnosis.

The triggering of interest and creation of broad intention to change (at least among initial champions and leaders) typically takes a year or two depending on the existing level of convergence and the willingness to collaborate. Critical activities revolve around building the foundations for change: establishing dialogue and trust between partners, including joint reflection and analysis of the main challenges at national and more local levels. IRC's EMPOWERS and Triple-S project resulted in a number of tools that can help support this process: the framework for stakeholder dialogue, the principles framework and the sustainability assessment tool for diagnosing what's working and what's not, and guidelines to support shared visioning, scenario building and strategic planning.

The intensity of these activities will drop off over time but will continue to be required in some form throughout the change process – as new challenges arise and actors enter the playing field. A critical outcome of this phase is the shared vision of success or the end state that is desired by all stakeholders.

Phase 2: revolves around learning and testing: searching for practical, actionable solutions to long-term, underlying problems that are preventing either universal access to, or the sustainability of, services. These are likely to be both strategic and more operational: updating or harmonising existing policy and legislation that may be absent or incomplete; and/or trialing and testing, through action research, new ways of monitoring for service delivery, improving asset management, creating demand for sanitation, clarifying roles and mandates at the local level and so on.

The learning and testing can take the form of more formal experiments or trials, or can be based on case studies or more anecdotal methodologies. Critically, learning and research at the local level needs to be constantly fed-back into national dialogue and policy review processes. Tools available to support this phase of the process include: classification and documentation guidelines for experiments.

Phase 3: in this phase the fruits of the change process really start to materialise through the impacts of systemic improvements to both policy and practice and the adoption and replication of good practice. The whole point of our way of working is that scale emerges through an internalisation of the activities and processes identified during the phase of learning and testing. Because key national and local stakeholders are actively involved in all aspect of planning, designing and executing the research, they are much more likely to recognise and accept the outputs as their own and embrace the change, rather than seeing it as imposed by external organisations and their global 'experts' and 'consultants'.

There are a number of crosscutting activities that play at least some role in all phases of change and indeed in creating water and sanitation sectors that can continue to advance and improve over time: aid effectiveness, advocacy and communication, and learning. In countries where the bulk of capital expenditure comes from aid, improving aid effectiveness and putting government squarely in the driver's seat is often the first step to any sort of meaningful change. Advocacy and communication are a large part of the work in bringing actors together around a common vision and in communicating solutions and spurring action. And building a sector that can learn and adapt is fundamental not only to diagnose and solve problems but to long-term sustainability. The are a number of tools and guidelines that can help strengthen these critical functions: guidelines for establishing learning alliances, and many more emerging from the EMPOWERS programme.

One of the most important roles in the change process is that of a hub or backbone. This could be a single organisation – it's a role that IRC often plays – or a consortium. The hub or backbone helps to pull actors together, get them moving in the same direction, and sustain forward momentum by building consensus, supplying and communicating evidence, strengthening learning and generally supporting the sort of process described above.

The figure above represents a highly conceptualised abstraction of the reality of sector change processes. In practice these are messy and never linear. They do not follow neat predictable lines; intense activity can proceed for long periods of time with seemingly no impact, and then change comes in a rush. The entire process can take 10 years or more.

Because most aid projects are conceived as stand-alone initiatives and have only three or four years to deliver, they are often unable to invest in some of the critical activities in phases 1 and 3. And, indeed, by the standards of many 'projects' the work we do can be seen as 'slow', not producing immediate (or immediately measurable) impact. All of which flies in the face of aid delivery as 'value for money' at the superficial level of maximising beneficiary numbers.

But we are convinced, through our experiences and those of others, that such an approach does, in the long-term, deliver results in terms of adoption, scale up and indeed impact. More importantly we consider that this approach is really the only game in town in terms of providing an exit strategy for aid.