Which factors in the enabling environment and which links between actors are key to achieving reliable sanitation services?

Published on: 30/01/2017

Tanzania did not reach the Millennium Development Goal (MDG) concerning improved sanitation facilities in 2012 (JMP Report 2014). Several years later – in the era of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) – there is still a lot to be done in the sanitation sector.

Angela Huston (IRC Programme Officer) and Sara Gabrielsson* (PhD in the field of Sustainability Science) are working on an upcoming book chapter about deconstructing the complexities that perpetuate poor water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) services in East Africa. Departing from Sustainability Science, the chapter aims to identify which factors in the enabling environment are key to achieving reliable WASH services. This article highlights Huston's and Gabrielsson's insights into this topic.

There are several aspects contributing to failure in the sanitation sector such as:

"Insanity is doing the same thing over and over while expecting different results."

- Albert Einstein

According to Huston and Gabrielsson the real problem lies within the way the failures are addressed. Actors in the sanitation sector often rush to solutions without fully grasping the problem. Without complete understanding of the problem it is not possible to learn from previous mistakes. And it is exactly this learning process that is essential to improving WASH services.

Therefore Huston and Gabrielsson advocate it is time for a new approach to 'view and do' sanitation. In order to do so, they make use of Sustainability Science. This science 'builds toward an understanding of the human–environment condition with the dual objectives of meeting the needs of society while sustaining the life support systems of the planet' (Turner et al., 2003, p. 8074).

Sustainability Science can be problem-oriented or solution-oriented. In the first mode problems are analysed in coupled-human environment systems. Problems are often seen as uncertain and complex. In the solution-oriented mode, however, problems are analysed in a critical and normative way in order to produce practical solutions.To realise this, participatory analyses are done – for example by including non-academics. Also, alternative pathways are explored.

The sanitation sector can benefit from Sustainability Science because the two fields relate to each other in the following ways:

Rigid institutional structures and policies can form barriers for achieving actionable knowledge. Actors within the sanitation sector remain trapped within the silos of specific disciplines or a single ministry which prevents collaborative actions or the recognition of possible synergies. They must focus on quantifiable outcomes in order to secure project-based funding that hampers sustainable and creative innovation.

There are however signs of change. '[...] small-capacity building networks, including research organizations from developing countries, seem to be promising venues [...]' (Wiek, Ness, Schweizer-Ries, Brand & Farioli, 2012, p.22).

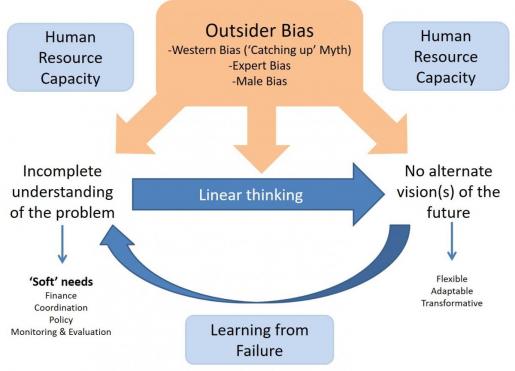

Figure 1 visualises how this can be put into practice in the sanitation sector in order to break the circle of failure.

The sector at large has progressed toward recognising that there is a 'failure trap' in sanitation. But it is important that the actors within the sector take an iterative look at the root causes of failure by adopting a systems thinking approach.

In the book chapter the authors recognise and deconstruct the approaches used by promising locally-developed innovators in an effort to understand why and how these approaches to the sanitation challenge may prove successful. As international actors working from an outsider's perspective, the authors aim to reconcile how and why biases have contributed to failure, and to use a holistic sustainability science approach to better understand our departure point and thus work toward a more sustainable future.

*Sara Gabrielsson is Assistant Professor at Lund University, Sweden and co-coordinator of the SIDA funded collaborative capacity building programme Sustainable Sanitation in Theory and Action (SUSTAIN) at University of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. She holds a PhD in the field of Sustainability Science, which attempts to bridge the gap between the natural and social sciences to produce actionable knowledge to sustain both people and the environment.

Wiek, A., Ness, B., Schweizer-Ries, P., Brand, F. S., Farioli, F. (2012). From complex systems analysis to transformational change: a comparative appraisal of sustainability science projects. Sustainability Science, 7(1), 5-24.

Turner, B. L., Kasperson, R. E., Matson, P. A., McCarthy, J. J., Corell, R. W., Christensen, L., ... & Polsky, C. (2003). A framework for vulnerability analysis in sustainability science. Proceedings of the national academy of sciences, 100(14), 8074-8079.