In an increasingly urbanising world, with an estimated 863 million people living in slum-like conditions in 2012 (UN, 2013), there is a clear need to start tackling one of the most pressing issues of urbanisation: the sanitation problem that arises when a large number of people are living together in a dense urban environment. IRC is stepping up its efforts in the field of urban sanitation. In his first blog post, our urban sanitation trainee, sets out the scene and proposes some directions for future work.

Published on: 05/06/2014

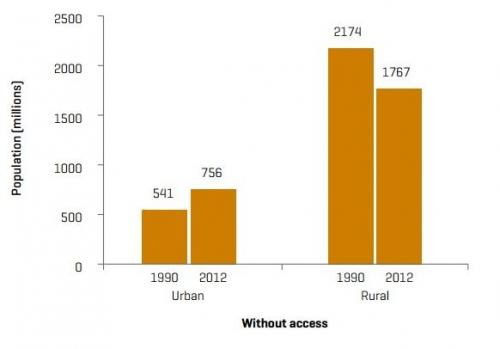

For a long time, the international development sector has considered sanitation as a mainly rural problem. In fact, as the latest update of the WHO/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Programme (JMP) shows, most people without access to improved sanitation facilities (still) live in rural areas (see figure 1). However, these figures also show that the number of urban dwellers without access to sanitation facilities is growing, not diminishing.

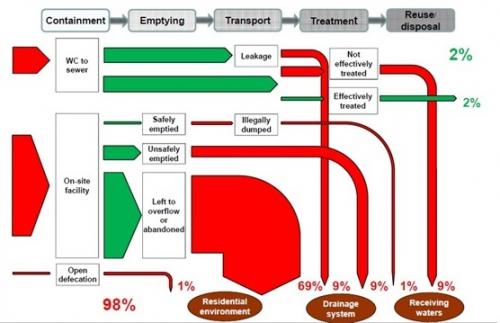

However, if we start looking beyond the number of people with access to sanitation facilities, the picture becomes even grimmer. On the one side, there is a need to consider the full sanitation chain: in urban areas, where population densities are high, the safe transport, treatment and disposal/reuse of faecal matter is just as important as its safe containment (e.g. in a latrine or toilet). Not taking the complete sanitation chain into account, will merely shift the health risks and environmental burden associated with faecal matter. A recent study by Baum et al. shows that the JMP figures regarding sanitation are likely to be much lower in urban areas if these are compiled to include wastewater treatment (Baum et al. 2013). If the figures for non-sewered sanitation are also taken into account it becomes clear that some cities at literally surrounded by their own faeces (WSP, 2014; see also figure 2).

On the other side, there is also a need to consider sanitation as a service. For a sanitation facility to be functional it needs to be accessible to all users and well maintained and cleaned in order to be hygienic and reliable. This may seem obvious, but the devil is in these little details: a recent study in Dar es Salaam (Jenkins et al. 2014) has found that despite the presence of sanitary facilities which meet the criteria used by the JMP, only a small fraction could be considered as “hygienically safe and sustainable sanitation”.

In other words, the JMP figures of those without access to ‘improved’ sanitation in urban areas (756 million in 2012) are likely to be a gross underestimation if we add up those that do not have access to a “hygienically safe and sustainable” facility, and those that live in cities where most of the human waste is unsafely disposed of in the open environment.

In the face of societal problems that require immediate attention, as the issues around urban sanitation do, a very human reaction is to go for immediate action and ‘do something’. In the past, this has often come in the form of technological interventions. Unfortunately, time has taught us that there is no ‘silver bullet’; interventions that merely transfer a technology from North to South have failed on many occasions (e.g. Murray & Drechsel 2011). This is why I believe it to be worthwhile to start off by understanding the reasons why urban sanitation came to be such a large problem in the first place.

One of the most common explanations given for the lack of basic services such as water and sanitation in large parts of urban areas, is that urban population has grown at a far higher rate than any municipal planning office can possibly keep up with. There is no denying that many municipalities will lack the resources to constantly expand their infrastructural networks, especially in hard to reach and dense areas where many settlements spring up. However, this cannot explain why some settlements are lacking services decades after they have been established.

One way to start is by considering the relationships between sanitation and the planning of the urban space. A lesson that has been learnt the hard way, is the importance to avoid static ‘one size fits all’ approaches. The reality is that there are, and there will always be, various types of toilets and latrines (e.g. private, public, communal), as well as different types of technologies (e.g. on- and off-site). All these systems will somehow have to be taken into account when developing an urban masterplan. Likewise, there will also be a need to acknowledge various types of treatment systems, which for instance make it feasible for small-scale desludging businesses to operate a profitable enterprise; which will never be the case if small trucks have to drive back and forth to remote treatment plants.

Even more important to acknowledge are the, at times messy, connections between sanitation and urban governance. This starts with the fragmented institutional set-up around sanitation, as responsibilities are typically divided amongst public health and environmental departments. A start would be to integrate planning approaches by taking the variety of waste flows into account (solid waste, ‘grey’ water, stormwater and human waste); these converge in dense urban spaces, but the responsibility hereof is also shifted between different municipal departments.

It becomes more difficult when we start considering the issues around tenancy; absent homeowners may not be willing to invest in sanitary facilities and tenants may not be willing to pay a higher rent that comes with a new latrine. WSUP has experience in this field (find their publications here).

Things get really complicated when disputes around land tenure become involved. So-called ‘informal’ areas may be denied public services by municipal authorities, on the basis that this would condone illegal squatting practices. However, this has rarely led to these squatters leaving voluntarily. In fact, as politicians are interested in the votes of these poor communities, a system of ‘vote- banks’ has emerged: politicians are elected on the basis of services delivered to a community, which in turn votes as a single block for this politician (Baken 2003). Needless to say, these services are flimsy at best, as the time horizon of politicians is not conducive to providing long-lasting services. On the other side, residents of an illegal settlement may oppose slum upgrading programmes that will result in the demolition of their houses without appropriate compensation (Smet 2008).

As if this weren’t enough, the urban sanitation sector is also riddled with vested interests. This has been the case since the time of the Ancient Romans (Vespasian’s’ pecunia non olet) and to date stories can be found where public toilets are used for the generation of excessive profits (see this interesting case from Germany). In other instances, politicians and construction companies may collude for the construction of public toilets, as described in Suketu Mehta’s Maximum City:

“Mama points out the advantages of backing him to his contributors. ‘Give five lakhs,’ he says to a potential donor in the construction business. ‘And I’ll get your five lakhs back to you within five days of getting elected. I’ll pass one toilet block.’ The contract to build it would go to the donor.” (Mehta, 2005; p104)

In other words it’s clear that urban sanitation is not only a large problem, it‘s also a complicated mess. The question which then arises is where to possibly start, in such a complex environment.

One of the tasks I was given when starting off as an urban sanitation trainee within IRC, was to figure out what IRC’s niche could be in the field of urban sanitation. In fact, many organisations working in this field have their niche, be it a product, service or geographical focus. Our collective assumption is that with all the combined niches we’re able to cover the wide range of issues to be tackled within the umbrella of urban sanitation. But what if this is not the case? What if we all get really good at our own little niche, but the larger problem isn't solved? For me, it is increasingly becoming clear that there is a need for a whole system change, so maybe the ‘whole’ should be IRC’s ‘niche’. How to do that? Well that’s the hard part. Soon I’ll provide more ideas on how to take this whole system approach in urban sanitation further. Until then, please contribute with your own thoughts or suggestions.

References

Baken, R.J., 2003. Plotting, Squatting, Public Purpose, and Politics: Land Market Development, Low Income Housing, and Public Intervention in India, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd.

Baum, R., Luh, J. & Bartram, J., 2013. Sanitation: a global estimate of sewerage connections without treatment and the resulting impact on MDG progress. Environmental science & technology, 47(4), pp.1994–2000. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23323809.

Jenkins, M.W. et al., 2014. Beyond “improved” towards “safe and sustainable” urban sanitation: assessing the design, management and functionality of sanitation in poor communities of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Journal of Water, Sanitation and Hygiene for Development, 4(1), p.131. Available at: http://www.iwaponline.com/washdev/004/washdev0040131.htm [Accessed May 14, 2014].

Murray, A. & Drechsel, P., 2011. Why do some wastewater treatment facilities work when the majority fail? Case study from the sanitation sector in Ghana. Waterlines, 30(2), pp.135–149. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.3362/1756-3488.2011.015.

Smet, J., 2008. Political and Social Dynamics in Upgrading Urban Sanitation a case from Colombo, Sri Lanka. I. In RC Symposium 2008 “Sanitation for the urban poor” Partnerships and Governance. Delft, The Netherlands, 19-21 November 2008. IRC International Water and Sanitation Centre. Available at: http://www.switchtraining.eu/fileadmin/template/projects/switch_training/files/Resources/Smet_2008_Urban_sanitation_in_Colombo.pdf.

United Nations (2013) Goal 7: Ensure Environmental Sustainability Accessible at: http://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/environ.shtml

WHO/UNICEF, 2014. Progress on sanitation and drinking-water - 2014 update, Geneva. Available at: http://www.wssinfo.org/fileadmin/user_upload/resources/JMP_report_2014_webEng.pdf.

WSP, 2014. Fecal Sludge Management in 12 Cities - Review Findings and Next Steps, Washington. Available at: http://wsp.org/sites/wsp.org/files/publications/WSP-Fecal-Sludge-12-City-Review-Research-Brief.pdf.

At IRC we have strong opinions and we value honest and frank discussion, so you won't be surprised to hear that not all the opinions on this site represent our official policy.